What Do We Have Of The Original Manuscripts Of The Word Of God

There are many skeptics who claim that The Ancient Manuscripts of Scripture are incomplete or that the original translators used manuscripts that were corrupt in one fashion or another, and so the Hebrew, Greek, and English works we have today are not The Word of God and the world is in need of additional works to clear up the errors. While it is true that one can not buy a version of a translation that is The Perfect Word of God, we believe God has so protected His Word through the ages that the diligent student of The Scriptures may find His Words and eat them (Jer. 15:16) and be filled with The Bread of Life (John 6:48-51) the joy and rejoicing of their heart (Jer. 15:16).

As an example of those who feel our manuscripts are deficient and the need for additional translations, we cite how the NIV (New International Version) regards Mark 16:9-20 as not being in the "reliable early manuscripts." Here is a direct quote: "The most reliable early manuscripts and other ancient witnesses do not have Mark 16:9-20.” Thus, the NIV translators suggest that these verses do not belong, a claim many have supported to the consternation of some believers. Many ancient Greek classes claim that these verses "clearly" do not belong in The Scriptures and that The Book should end with Mark 16:8 and the women running from the tomb in unbelief. Before we consider these "scholars" theories as Truth, let's consider the evidence.

When we are confronted with a charge against some passage of The Bible, it is imperative that we collect all the evidence in the matter before we attempt to make a judgment on its validity. What are these "ancient Greek manuscripts" that do not contain these verses in The Gospel of Mark? How old are they, how many are there, and how authoritative are they? For the answer to this argument, we would like to quote in part a passage by Dr. E.W. Bullinger in his Appendices to the Companion Bible. He examines this question in detail and reveals to us what the evidence for and against this passage actually is. (Note: Bullinger uses "MSS." as an abbreviation for "manuscripts.”)

As To The Greek Manuscripts, there are none older than the fourth century, and the oldest are two Uncial MSS. that do not contain those twelve verses. Of all the others (consisting of some eighteen Uncials and some six hundred Cursive MSS. which all contain the Gospel of Mark), not one leaves out these twelve verses.

So the score is 2 - Against and 618 - For. This evidence and the fact that if this were a sport's score, it would be game over with an obvious winner. One must admit the numbers prove rather overwhelming evidence in favor of the passage's validity. But the evidence does not stop there, so let's explore what additional evidence Dr. Bullinger can share with us.

There are translations of The Bible into other languages that are far older than our most ancient Greek manuscripts:

Ancient Translations of The Bible and their Versions:--

The Syriac. The oldest is the Syriac in its various forms: the "Peshitto" (century 2) and the "Curetonian Syriac" (century 3). Both are older than any Greek MS. in existence.

The Latin Versions. Jerome (A.D. 382), who had access to Greek MSS. older than any now extant, this Version (known as the Vulgate) was only a revision of the Vetus Itala, which is believed to belong to century 2.

The Gothic Version (A.D. 350).

The Egyptian Versions: the Memphitic (or Lower Egyptian, less properly called "Coptic"), belonging to century 4 or 5, and the "Thebaic" (or Upper Egyptian, less properly called the "Sahidic"), belonging to century 3.

The Armenian (century 5), The Ethiopic (century 4-7), and the Georgian (century 6).

One of the versions of particular note is the Syriac that Dr. Bullinger mentioned above, which is a version translating the Bible into Aramaic, the common language of Israel at the time, and which dates from the second century when it was first translated. Thus, the Syriac is two hundred years older than the two oldest Greek manuscripts that do not contain these verses. This should raise serious questions about those two oldest Greek manuscripts and those who use them to "prove" that the verses in question did not originally exist in Mark's Gospel and were added later. How could these verses have been added after the fourth century into our Greek Bibles if they already existed two hundred years BEFORE they were supposedly added in? We would like to hear about anything that existed two hundred years before it was created. That would be an interesting thing indeed. But the evidence does not stop there. Let us go on with Dr. Bullinger.

THE FATHERS. Whatever may be the value (or otherwise ) of their writings as to doctrine and interpretation must be studied yet, in the determination of actual words or their form, or sequencing of their evidence, even by an allusion, as to whether a verse or verses existed or not in their day, these books can be more valuable than even manuscripts or Versions.

There are nearly a hundred ecclesiastical writers older than the oldest of our Greek codices, while between A.D. 300 and A.D. 600, there are about two hundred more.

Here are just a few:

Papias (about A.D. 100).

Justin Martyr (A.D. 151).

Irenaeus (A.D. 180).

Hippolytus (A.D. 190-227).

Vincentius (A.D. 256) .

The Acta Pilati (century 2).

The Apostolical Constitutions (century 3 or 4).

Eusebius (A.D. 325).

Aphraartes (A.D. 337).

Ambrose (A.D. 374-97).

Chrysostom (A.D. 400).

Jerome (b. 331, d. 420).

Augustine (fl. A.D. 395-430).

Nestorius (century 5).

Cyril Of Alexandria (A.D. 430).

Victor Of Antioch (A.D. 425) confutes the opinion of Eusebius by referring to very many MSS. which he had seen.

The Bible claims to be The Word of God, coming from Himself as His Revelation to man. If these claims are not true, then The Bible cannot be even "a good book." In this respect, "The Living Word" is like The Written Word, for if the claims of The Lord Jesus being God are not True, He could not even be "a good man." As to those claims, man can believe them or leave them. In the former case, he goes to The Word of God and is overwhelmed with an abundance of evidence of its Truth; in the latter case, he abandons Divine Revelation for man's imagination.

In Divine Revelation "holy men spake from God as they were moved (or borne along) by the Holy Spirit" (2 Pet. 1:21). The wind, as it is borne along among the trees, causes each tree to give forth its own peculiar sound, so that the experienced ear of a woodman could tell, even in the dark, the name of the tree under which he might be standing, and distinguish the creaking elm from the rustling aspen. Even so, while each "holy man of God" is "moved" by One Spirit, the individuality of the inspired writers is preserved. Thus, we may explain the medical words of "Luke the beloved physician" used in his Gospel and in the Acts of the Apostles (Col. 4:14).

As to Inspiration itself, we have no need to resort to human theories or definitions, as we have a Divine definition in Acts 1:16, which is all-sufficient. "This scripture must needs have been fulfilled, which the Holy Ghost, by the mouth of David, spake before concerning Judas." The reference is to Psalm 41:9.

It is "by the mouth" and "by the hand" of holy men that God has spoken to us. Hence, it was David's voice and David's pen, but the words were not David's words.

Nothing more is required to settle the faith of all believers, but it requires Divine operation to convince unbelievers; hence, it is vain to depend on human arguments.

As To Language

With regard to this, it is generally assumed that because The New Testament comes to us in Greek, the N.T. ought to be in classical Greek and is then condemned because it is not! Classical Greek was at its prime some centuries before, and in the time of our Lord, there were several reasons why the N.T. was not written in classical Greek.

The writers were Hebrews; thus, while the language is Greek, the thoughts and idioms are Hebrew. These idioms or Hebraisms are generally pointed out in the notes of The Companion Bible. Most readings will be accounted for and understood if the Greek of the N.T. is regarded as an inspired translation from Hebrew or Aramaic originals.

Then we have to remember that in the time of our Lord, there were no less than four languages in use in Palestine, and their mixture formed the "Yiddish" of those days.

There was HEBREW, spoken by Hebrews;

There was GREEK, which was spoken in Palestine by the educated classes generally;

There was LATIN, the language of the Romans, who then held possession of the land;

And there was ARAMAIC, the language of the common people.

Doubtless, our Lord spoke all these (for we never read of Him using an interpreter). In the synagogues, He would necessarily use Hebrew; to Pilate, He would naturally answer in Latin; while to the common people, He would doubtless speak in Aramaic.

ARAMAIC was Hebrew, developed during and after the Captivity in Babylon. There were two branches, known roughly as Eastern (which is Chaldee) and Western (Mesopotamian or Palestinian). This latter was known also as Syriac, and the Greeks used "Syrian" as an abbreviation for Assyrian. The early Christians perpetuated this. Syriac flourished till the seventh century A.D. In the eighth and ninth, it was overtaken by the Arabic, and by the thirteenth century, it had disappeared. We have noted that certain parts of the O.T. are written in Chaldee (or Eastern Aramaic). Ezra 4:8-6:18; Ezra 7:12-26; Dan. 2:4-7:28. Cp. also 2 Kings 18:26.

Aramaic is of three kinds:-- 1. Jerusalem. 2. Samaritan. 3. Galilean.

Of these, Jerusalem might be compared with High German and the other two with Low German.

There are many Aramaic words preserved in the Greek of the N.T., and most of the commentators call attention to a few of them; but, from the books cited below, we are able to present a more or less complete list of the examples to which attention is called in the notes of The Companion Bible.

Abba. Mark 14:36; Rom. 8:15; Gal. 4:6.

Ainias. Acts 9:33-34.

Akeldama. Acts 1:19. Akeldamach (LA). Acheldamach (T Tr.). Hacheldamach (WH). See Ap. 161. I. Aram. Hakal dema', or Hakal demah .

Alphaios. Matt. 10:3; Mark 2:14; Mark 3:18; Luke 6:15; Acts 1:13.

Annas. Luke 3:2; John 18:13; John 18:24; Acts 4:6.

Bar-abbas. Matt. 27:16-17; Matt. 27:20-21; Matt. 27:26; Mark 15:7; Mark 15:11; Mark 15:15; Luke 23:18; John 18:40.

Bartholomaios. Matt. 10:3; Mark 3:18; Luke 6:14; Acts 1:13.

Bar-iesous. Acts 13:6.

Bar-iona. Matt. 16:17.

Bar-nabas. Acts 4:36; &c. 1Cor. 9:6; Gal. 2:1; Gal. 2:9; Gal. 2:13; Col. 4:10.

Bar-sabas. Acts 1:23; Acts 15:22 (Barsabbas all the texts).

Bar-timaios. Mark 10:46.

Beel-zeboul. Matt. 10:25; Matt.12:24-27; Mark 3:22; Luke 11:15-19.

Bethesda. John 5:2. (Bethzatha, T WH; Bethsaida, or Bethzather , L EH Rm.)

Bethsaida. Matt. 11:21; Mark 6:45; Mark 8:22; Luke 9:10; Luke 10:13; John 1:44; John 12:21.

Bethphage. Matt. 21:1; Mark 11:1; Luke 19:29.

Boanerges. Mark 3:17. (Boanerges, L T Tr. A WH.)

Gethsemanei. Matt. 26:36; Mark 14:32.

Golgotha. Matt. 27:33; Mark 15:22; John 19:17.

Eloi. Mark 15:34.

Ephphatha. Mark 7:34.

Zakchaios. Luke 19:2-8.

Zebedaios. Matt. 4:21; Matt.10:2; Matt. 20:20; Matt. 26:37; Matt. 27:56; Mark 1:19; Mark 3:17; Mark 10:35; Luke 5:10; John 21:2.

Eli. Matt. 27:46. (Elei (voc.), T WH m.; Eloi WH.)

Thaddaios. Matt. 10:3; Mark 3:18.

Thomas. Matt. 10:3; Mark 3:18; Luke 6:15; John 11:16; John 14:5; John 20:2-29; John 21:2; Acts 1:13.

Ioannes. John 1:42; John 21:15-17. (Ioanes, Tr. WH.) See Bar-iona . (Iona being a contraction of Ioana.)

Kephas. John 1:42; 1 Cor. 1:12; 1 Cor. 3:22; 1 Cor. 9:5; 1 Cor. 15:5; Gal. 2:9.

Kleopas. Luke 24:18.

Klopas. John 19:25.

Lama. Matt. 27:46; Mark 15:34. (Lema, L. Lema, T Tr. A WH).

Mammonas. Matt. 6:24. Luke 16:9, 11, 13. (Mamonas, L T Tr. A WH.)

Maran-atha. 1Cor. 16:22 ( = Our Lord, come!). Aram. Marana' tha'.

Martha. Luke 10:38; Luke 10:40; Luke 10:41; John 11:1, &c.

Mattaios. Matt. 9:9; Matt. 10:3; Mark 3:18; Luke 6:15; Acts 1:13; Acts 1:26. (All the critics spell it Maththaios.)

Nazareth (- et). Matt. 2:23; Matt. 4:13 (Nazara, T Tr. A WH); Matt. 21:11; Mark 1:9; Luke 1:26; Luke 2:4; Luke 2:39; Luke 2:51; Luke 2:4:16 (Nazara. Omit the Art. L T Tr. A WH and R.) John 1:45-46; Acts 10:38.

Pascha. Matt. 26:2; Matt. 26:17-19; Mark 14:1; Mark 14:12-16; Luke 2:41; Luke 22:1-15; John 2:13; John2:23; John 6:4; John 11:55; John 12:1; John 13:1; John 18:28; John 18:39; John 19:14; Acts 12:4; 1Cor. 5:7; Heb. 11:28. The Hebrew is pesak.

Rabboni, Rabbouni (Rabbonei, WH). Mark 10:51; John 20:16.

Raka. Matt. 5:22. (Reyka' is an abbreviation of Reykan.)

Sabachthani. Matt. 27:46; Mark 15:34; (Sabachthanei, T Tr. WH.)

Sabbata (Aram. sabbata'). Heb. shabbath. Matt. 12:1; Matt. 12:5; Matt. 12:10-12, &c.

Tabitha. Acts 9:36; Acts 9:40.

Talithakumi. Mark 5:41; (In galilaean Aramaic it was talitha' kumi .)

Hosanna (in Aram. = Save us; in Heb. = Help us). Matt. 21:9-15; Mark 11:9-10; John 12:13.

The Papyri And Ostraca

Besides, the Greek text mentions ought to be made of these, although it concerns the interpretation of the text rather than the text itself. We have only to think of the changes that have taken place in our own English language during the last 300 years to understand the inexpressible usefulness of documents written on the material called papyrus and on pieces of broken pottery called ostraca, recently discovered in Egypt and elsewhere. They are found in the ruins of ancient temples and houses and in the rubbish heaps of towns and villages and are of great importance.

They consist of business letters, love letters, contracts, estimates, certificates, agreements, accounts, bills of sale, mortgages, school exercises, receipts, bribes, pawn tickets, charms, litanies, tales, magical literature, and literary production.

These are of inestimable value in enabling us to arrive at the true meaning of many words (used in the time of Christ) that were heretofore inexplicable. Examples may be seen in the notes on "scrip" (Matt. 10:10; Mark 6:8; Luke 9:3), "have" (Matt. 6:2, Matt. 6:5, Matt. 6:16. Luke 6:24. Philem. 1:15); "officer" (Luke 12:58); "presseth" (Luke 16:16); "suffereth violence" (Matt. 11:12), &c.

The Manuscripts of the Greek New Testament dating from the fourth century A.D. are more in number than those of any Greek or Roman author, for these latter are rare, and none are really ancient, while those of the N.T. have been set down by Dr. Scrivener at not less than 3,600, a few containing the whole, and the rest various parts, of the N.T.

The study of these from a literary point of view has been called "Textual Criticism," it necessarily proceeds altogether on documentary evidence, while "Modern Criticism" introduces the element of human opinion and hypothesis.

Man has never made proper use of God's gifts. God gave men the sun, moon, and stars for signs and seasons to govern the day, the night, and the years. But no one today can tell us what year (Anno Mundi ) we are actually living in! In like manner, God gave us His Word, but man compassed with infirmity, has failed to preserve and transmit it faithfully.

The worst part is that man charges God with the result and throws the blame on Him for all the confusion due to his own want of care. From very early times, the Old Testament had official custodians of the Hebrew text. Its Guilds of Scribes, Nakdanim, Sopherim, and Massorites elaborated plans by which the original text had been preserved with the greatest possible care. But though, in this respect, it had advantages that the Greek text of the N.T. never had, it nevertheless shows many signs of human failure and infirmity. Man has only to touch anything to leave his mark upon it. Hence, the MSS of the Greek Testament is to be studied today with the utmost care. The materials are:--

The MSS. themselves in whole or in part.

Ancient versions were made from them in other languages.

Citations made from them by early Christian writers long before the oldest MSS we possess (see Ap. 168).

As to the MSS. themselves, we must leave all palaeographical matters aside (such as having to do with paper, ink, and calligraphy) and confine ourselves to what is material.

These MSS. consist of two great classes : (a) Those written in Uncial (or capital) letters and (b) those written in "running hand," called Cursives. The former is considered more ancient, although it is obvious and undeniable that some cursives maybe transcripts of Uncial MSS. more ancient than any existing Uncial MSS.

This will show that we cannot depend altogether upon textual criticism. It is more to our point to note that what are called "breathings" (soft or hard) and the accents are not found in any MSS. before the seventh century (unless they have been added by a later hand).

Punctuation also, as we have it today, is entirely absent. The earliest two MSS (known as B, the MS. in the Vatican, and the Sinaitic MS., now at St. Petersburg) have only an occasional dot, and this is on a level with the top of the letters. The text reads on without any divisions between letters or words until MSS. of the ninth century, when (in Cod. Augiensis, now in Cambridge) there is seen for the first time a single point that separates each word. This dot is placed in the middle of the line but is often omitted.

None of our modern punctuation marks are found until the ninth century, and only in Latin versions and some cursives. From this, it will be seen that the punctuation of all modern editions of the Greek text, and of all versions made from it, rests entirely on human authority and has no weight whatever in determining or even influencing the interpretation of a single passage. This refers also to the employment of capital letters and to all the modern literary

refinements of the present day.

Chapters also were alike unknown. The Vatican MS. makes a new section where there is an evident break in the sense. These are called titloe, or kephalaia.

There are none in a (Sinaitic), see above. They were not found till the fifth century in Codex A (British Museum), Codex C (Ephraemi, Paris), and Codex R (Nitriensis, British Museum) of the sixth century. They are quite foreign to the original texts. For a long time, they were attributed to HUGUES DE ST. CHER (Huego de Sancto Caro), Provincial to the Dominicans in France, and afterward a Cardinal in Spain, who died in 1263. But it is generally believed that they were made by STEPHEN LANGTON, Archbishop of Canterbury, who died in 1227. It follows, therefore, that our modern chapter divisions are also destitute of MS. authority.

As to verses in the Hebrew O.T., these were fixed and counted for each book by the Massorites, but they are unknown in any MSS. of the Greek N.T. There are none in the first printed text in The Complutensian Polyglot (1437-1517), in the first printed Greek text (Erasmus, in 1516), or in R. Stephens's first edition of 1550. Verses were first introduced in Stephens's smaller (16mo) edition, published in 1551 at Geneva. These also are, therefore, destitute of any authority.

The Printed Editions Of The Greek Text

Many printed editions followed the first efforts of ERASMUS. Omitting the Complutensian Polyglot mentioned above, the following is a list of all those of any importance:--

1. Erasmus (1st Edition) 1516

2. Stephens 1546-9

3. Beza 1624

4. Elzevir 1624

5. Griesbach 1774-5

6. Scholz 1830-6

7. Lachmann 1831-50

8. Tischendorf 1841-72

9. Tregelles 1856-72

10. Alford 1862-71

11. Wordsworth 1870

12. Revisers' Text 1881

13. Westcott and Hort 1881-1903

14. Scrivener 1886

15. Weymouth 1886

16. Nestle 1904

All of the above are "Critical Texts," and each editor has striven to produce more accurate text than his predecessors. Beza (No. 3 above) and the Elzevir (No. 4) may be considered as being the so-called "Received Text," which the translators of the Authorized Version used in 1611.

Rightly Dividing the Word as to its Literary Form

The "Word" comes to us in our English Translation. But it comes with much that is human in its Literary Divisions, and it is far from being rightly divided.

1. The Two Testaments.

"The Word of God" as a whole comes to us in two separate parts: one written originally in Hebrew, the other in Greek. Only in the Versions are these two combined and bound together in one Book.

These divisions, of course, are not human, though the names are by which they are commonly known.

Up to the second century, the Greeks used the term "Old Covenant" to describe the Hebrew Bible. This passed into the Latin Vulgate as "Vetus Testamentum," from which our English term "Old Testament" was taken.

By way of distinction, the Greek portion was naturally spoken of as the "New Testament." But neither of these names is Divine in its origin.

2. The Separate Books of the Bible.

When, however, we come to the Separate Books, though their origin is Divine, the human element is at once apparent.

(a) The Books of the Old Testament.—The Books as we have them today are not the same as in the Hebrew Canon, either as to their number, names, or order.

The change came about when the first Translation of the Hebrew Bible was made into Greek in the Version known as the Septuagint.

It was made in the latter part of the third century BC. The exact date is not known, but the consensus of opinion leans to about 286-285 BC.

It is the oldest of all the translations of the Hebrew Text, and its Divisions and arrangement of the Books have been followed in every translation since made.

Man has divided them into four classes: (1) The Law, (2) The Historical Books, (3) The Poetical Books, and (4) The Prophetical Books.

The Lord Jesus divides them into Three classes: (1) The Law, (2) The Prophets, and (3) The Psalms. And who will say that HE did not Rightly Divide them? But His Division was made according to the Hebrew Bible extant in His day, not according to man's Greek Translation of it—which was also extant at that time.

In the Hebrew Canon, these three Divisions contain twenty-four Books in the following order:—

(i) "The Law" (Torah)

These five books form the Pentateuch

1. Genesis

2. Exodus

3. Leviticus

4. Numbers

5. Deuteronomy

(ii) "The Prophets" (Neviim)

"The Former Prophets" (Zech 7)

6. Joshua

7. Judges

8. Samuel

9. Kings

The Latter Prophets

10. Isaiah

11. Jeremiah

12. Ezekiel

13. The Minor Prophets

(iii) "The Psalms" (K'thuvim) or the [other] writings

14. Psalms

15. Proverbs

16. Job

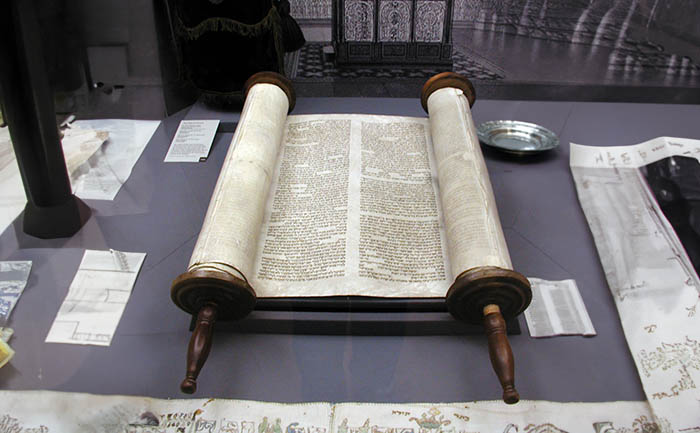

The Five "Megilloth" (or scrolls)

17. Song of Songs

18. Ruth

19. Lamentations

20. Ecclesiastes

21. Esther

22. Daniel

23. Ezra-Nehemiah

24. Chronicles

This is how the Books are Rightly Divided in the Hebrew Bible. And it is sad to find so many good men exercising their ingenuity in order to find some Divine spiritual teaching in the utterly human and different order of the Books given in the Translations. One actually manufactures "five Pentateuchs," quite dislocating the Books of The Bible, and he arbitrarily re-arranges them to suit his theory. Another divides them by re-arranging them in what he conceives to be the chronological order, which results in the Psalms being dispersed among the Historical Books, among other calamities.

The "Higher" Critics would have us make a Hexateuch instead of a Pentateuch.

We fear it is hopeless to look for the Books to be Rightly Divided and arranged in the order of the Hebrew Canon, so we shall have to make the best of man's having wrongly divided the Word of Truth from the outset.

The number of Concordances, Commentaries, and general works where reference is made to the present chapters and verses would be sufficient to make such a change impossible, however desirable it might be on other grounds.

Nevertheless, it is well for those who would study the Word of Truth to have this information and to be in possession of the facts of the case, even if the result is only to prevent them from attaching any importance to the present order of the Books, and keep them from elaborating some scheme of doctrine or theology based on what is only human in its origin.

(b) The Books of the New Testament.—As to the Books of the New Testament, the problem presented is somewhat different. We find them in the Manuscripts generally in five groups: (1) the Gospels, (2) the Acts, (3) the General Epistles, (4) Paul's Epistles, and (5) the Apocalypse.

The order of these groups varies in certain MSS, and the order of the Books in the different groups varies. There is, however, one exception that we have elsewhere pointed out: The Epistles of Paul addressed to Churches are always in the same order as we have them in our English Bible today. Out of the hundreds of Greek MSS, no one has ever seen where the Canonical order of these Epistles is different from that in which they have come down to us.

We can, therefore, build our teaching on a sure foundation, though we cannot do so on the order of the other New Testament books.

The Divisions of the Hebrew Text

The Hebrew Text is divided (in the MSS) into five different forms:—

(a) Into open and closed Sections, answering somewhat to our paragraphs. These were to promote facility in reading.

(b) Into Sedarim or the Triennial Pericopes;*, i.e., Portions marked off: so that the Pentateuch is divided into 167 Pericopes or "Lessons," which are completed in a course of three years' reading. There are 452 of these Seders** in the Hebrew Bible, indicated by p, in the margin.

* Greek, from peri (around) and kopto (cut); a portion or extract Pronounced Pe-ric'-o-pe.

** From (sadar), to arrange in order.

(c) Besides these, the Pentateuch was divided into 54 Par'shioth or Annual Pericopes, which the Law was read through once a year.

(d) The division into verses. The verses in the Hebrew Bible are of ancient origin and were noted by a stroke called Silluk under the last word of each verse.

These words were carefully counted for each book. Hence, the Scribes were so called not because of their writing (from the Latin word Scribo) but because they were called Sopherim or Counters (from the Hebrew, Sopher, to count). The Massorah gives the number of verses as 23,203.

The Divisions of the Greek Text

In the Greek MSS of the New Testament, sections are indicated in the margin, dividing the text according to the sense.

There is also a division of the Gospels ascribed to TATIAN (Century II.) called Kephalaia, i.e., heads or summaries: these are also known as Titloi or titles. In the third century, AMMONIUS divided the Text according to sections, known by his name: "The Ammonian Sections." In the fifth century, EUTHALIUS, a deacon of Alexandria, divided Paul's Epistles, the Acts, and the General Epistles into Kephalaia, and ANDREAS (Archbishop of Cæsarea in Cappadocia) completed the work by dividing the Apocalypse into 24 Logoi or paragraphs, each being again divided into three Kephalaia.

These dividings of the New Testament can be traced back to individual men and are all essentially human.

The Divisions of the Versions

(a) The Chapters.—There are other more modern divisions into Chapters. These are quite foreign to the Original Texts of the Old and New Testaments. They were attributed to Hughes De St. Cher (Hugo de Sancto Caro) for a long time. He was Provincial to the Dominicans in France and afterward a Cardinal in Spain: he died AD 1263. But it is generally believed that they were made by Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, who died in 1227.

(b) The Verses.—Hugo made use of Langton's chapters and added subdivisions, which he indicated by letters. This was in 1248. Robert Stephens, finding these letters inadequate, introduced numbers in their place in his Greek Testament of 1551. This was the origin of our verse divisions, which were first introduced into the English Version known as the Geneva Bible (1560) and into our Authorized Version in 1611. These verses do not always correspond with those of the Hebrew Bible.

(c) The Chapter Breaks—As to these chapter divisions, they were not of Jewish origin and were never associated with the Hebrew Bible until AD 1330, when Rabbi Salomon Ben Ismael adopted the Christian chapters by placing the numerals in the margin to facilitate reference for purposes of controversy.*

* This appears from a note appended to MS No. 15 in the Cambridge University Library. See Dr. Ginsburg's Introduction, etc., p. 25.

In many cases, they agree with the Massoretic divisions of the Hebrew Bible, though there are glaring instances of divergence.*

* Up to AD 1517, the Editors of the Printed Text of the Hebrew Bible closely adhered to the MSS and ignored the Christian or Gentile chapters.

The Editors of the Complutensian Polyglot of Cardinal Ximenes (1514-1517) were the first to reverse this practice, but still confining the indications to the margin in Roman Numerals.

Felix Pratensis was the first to substitute Hebrew Letters for the Roman Numerals in his Edition printed by Bomberg, Venice, in AD 1517, though he retained the Massoretic divisions.

Jacob Ben Chayim adopted the same practice in his standard Edition (AD 1524-5), and it was continued down to 1751, when

Arias Montanus actually went so far as to break up the Hebrew Text and insert the Hebrew Letters (or Numerals) into the body of the Text in his edition printed at Antwerp in 1571.

From this, the "pernicious practice," as Dr. Ginsburg well calls it, has continued in the Editions of the Hebrew Text since printed, though it is discarded in his own Massoretico-Critical Edition, printed in Vienna in 1894 and published by the Trinitarian Bible Society of 7, Bury Street, Bloomsbury, London.

It will thus be seen how very modern and human and how devoid of all authority the chapter and verse divisions obtain in the version of the Bible generally and in our English Bible in particular. Though they are most useful for purposes of reference, we must be careful never to use them for interpretation or for doctrinal teaching. They seldom accord with the breaks required by the Structure. Sometimes, they break the connection altogether; at other times, they materially affect the sense.

As examples, where the chapter breaks interfere with the Connection and the Sense, we may notice Genesis 1 and 2, where the Introduction (Gen. 1:1-2:4) is broken up, and the commencement of the first of the Eleven Divisions (or "Generations") is hidden. This wrong break has led to serious confusion. Instead of seeing Gen. 1:1-2:3, a separate Summary of Creation in the form of an Introduction, many think they see two distinct creations, while others see a discrepancy between two accounts of the same creation.

The break between 2 Kings 6 and 7 should come after 2 Kings 7:2; that is to say, 2 Kings 7:1-2 should be 2 Kings 6:34-35.

The break between Isaiah 8 and 9 is, to say the least, most unfortunate, dislocating, as it does, the whole sense of the passage.

Isaiah 53 should commence at Isaiah 52:13. This agrees with its Structure:

A. 52:13-15. The foretold exaltation of Jehovah's Servant, the Messiah.

B. 53:1-6. His rejection by others.

B. 7-10. His own sufferings.

A. 10-12. The foretold exaltation of Messiah.

Isaiah 52:1-12 should have been the concluding portion of chapter 51.

Jeremiah 3:6 begins a new prophecy which goes down to the end of chapter 6.

Matthew 9:35-38 should belong to chapter 10.

John 3 should commence with John 2:23, thus connecting the remarks about "men" with the "man of the Pharisees."

John 8:1 should be the last verse of chapter 7, setting in contrast the destination of the people and that of the Lord.

In Acts 4, the last two verses should have been the first two verses of chapter 5.

We can quite see that Acts 7 is already a long chapter; the break between it and Chapter 6 is unfortunate because the connection between "these things" in Acts 7:1 is quite severed from the "things" referred to in Chapter 6.

The same is the case in Acts 8:1. Also in Acts 22:1.

Romans 4 ought to have run on to Rom. 5:11, as is clear from the argument, as shown by the Structure.

In the same way, Romans 6 ought to run on and end with Rom. 7:6, which concludes the subject. The commencement of Rom. 7:7, "What shall we say then?" would thus correspond with Rom. 6:1.

Romans 15:1-7 really belongs to chapter 14.

1 Corinthians 11:1 should be the last verse of chapter 10.

2 Corinthians 6 should end with 2 Cor. 7:1, for 2 Cor. 7:2 commences a new subject and leaves the "promises" of 2 Cor. 7:1 to be connected with the rehearsal of them in chapter 6.

In the same way, Philippians 3 ought to end with Phil. 4:1 to complete the sense.

Colossians 3 should end with Col. 4:1. Thus, "masters" would follow and stand in connection with the exhortation to "servants," and Col. 4:2 would commence the new subject.

In 1 Peter 2:1, the word "wherefore" points to the fact that this verse is closely connected with chapter 1.

2 Peter 2:1, in the same way, concludes chapter 1, and the "false prophets" are contrasted with the Divinely inspired prophets.

In 2 Timothy 4:1, the force of the word "therefore" is quite lost by being cut off from the conclusion of chapter 3.

Revelation 3, as a break, ought to be ignored, as it quite dislocates the seven letters to the Assemblies.

Revelation 13:1 belongs to, and is the conclusion of, chapter 12. The break is thus actually made in the RV, and the correct reading of the Greek MSS followed shows the close connection of the words "and he [i.e., Satan] stood upon the sand of the sea" with Rev. 12:17, and also with chapter 13 as containing the result of Satan's thus standing.

In the same way, the break between Revelation 21 and 22 is unfortunate, as the real chapter break should correspond with the Structure and come between verses 5 and 6 of chapter 22.

Other examples may easily be found, but these will be sufficient to show the importance of "Rightly Dividing the Word of Truth," even as to the Chapter Divisions.

(d) The Chapter and Running Page-Headings.— When these chapter divisions are combined with (1) the chapter headings and (2) the running page headings, they become positively mischievous, partaking of the nature of interpretation instead of translation. Needless to say, we may absolutely disregard them, as they always aggravate the chapter break and often mislead the reader.

The running page headings are a fruitful source of mischief. Over Isaiah 29 (as we have said above), in an ordinary Bible, we read "God's judgments upon Jerusalem." On the opposite page, we read Isaiah 30, "God's mercies to his church." The same may be seen in the concluding chapters of Isaiah, both in the running page headings and in the chapter headings. But there is no break or change in the subject matter. It consists of all "the vision which Isaiah saw concerning Judah and Jerusalem" (Isa. 1:1). Here is a "dividing" of the Word. But, the question is, can it be called "rightly dividing" when God's "mercies" are claimed for the Church, and His "judgments" generously given over to the Jews? Such "dividing" of the Word can hardly be said to be "without partiality."

(e) Punctuation.—One other mode of dividing the Word as to its Literary Form is by Punctuation, which is a still more important manner of dividing the Word, as it seriously affects the Text by dividing its sentences and thus fixing its sense.

The importance of this will be seen when we note that its effect is to fasten the interpretation of the translator onto the Word of God by making his translation part of that Word. It thus comes to the ordinary reader as part and parcel of the Truth of God, whereas it is absolutely arbitrary and is wholly destitute of either Divine or human authority.*

* Sometimes, a change of punctuation may be made through inadvertence or through ignorance. We have heard of 1 Corinthians 9:24 being read aloud thus: "They that run in a race run. All but one receiveth the prize." The ignorance that perpetrated this failed to see the bad grammar, which resulted in the last clause.

The Greek Manuscripts have practically no punctuation system: the most ancient, none at all; and the later MSS nothing more than an occasional single point even with the middle or in line with the top of the letters. Where there is anything more than this, it is generally agreed that it is the work of a later hand.

So, in the Original Manuscripts, we have no guide whatever to any dividing of the Text, whether rightly or wrongly. Indeed, there is no division in the most ancient MSS, but there is not even any break between the words! So that we can find no help from the MSS.

When they came to be collated, edited, and printed, the respective Editors introduced a system of punctuation. Each one followed his own plan and exercised his own human judgment. No two editors have punctuated the text in the same way, so we have no help from them.

When we come to the English Authorized Version, we are still left without guidance or help.

The Authorized Version of 1611 is destitute of any authority, for the Translators punctuated only according to their best judgment. But even here, few readers are aware of the many departures that have been made from the original Edition of 1611 and how many changes have been made in subsequent Editions.*

* These changes affect not merely punctuation but the marginal notes and references, the uses of capital letters and italic type, orthography, grammatical peculiarities, etc.

Some of these differences arise doubtless from oversight, but other changes have been made undoubtedly with deliberate intent. No one can tell who made them or when they were introduced. A few, however, can be traced.*

* A full account of these may be seen in the Report of the Select Committee of the House of Commons on the Queen's Printers' Patent, 1859, a Blue Book full of interesting information; also in Dr. Scrivener's Preface to The Cambridge Paragraph Bible of 1873.

The edition of 1616 was the first edition of the AV which shows any considerable revision. The first Cambridge Editions of 1638 and 1639 appear to have been a complete revision, though done without authority.

The Edition of 1660 added many marginal notes. 1701 was the first to introduce the marginal dates, tables of Scripture measures and weights, &c.

The Edition of 1762 contained serious attempts at improvements made by Dr. Paris. He was the first to substitute a full stop for the colon of 1611 in Zechariah 11:7, after "staves." This edition considerably extended the use of Italic type and incorporated Bishop Lloyd's chronological notes.

Dr. Blayney's Edition of 1769 introduced many changes and glaring errors, which, unfortunately, have been followed without inquiry and suspicion. These imperfections led to a great controversy and a Public inquiry, which included the policy of the Royal Patent and the working of the University Presses.

A Revision of the American Bible Society (1847-1851) prepared the way for our English Revised Version (1881-1885).

The "Advertisement" to the Universities' Edition, called "The Parallel Bible" (of the RV and AV), fully endorses all we have said:—

"The left-hand column contains the text of the Authorized Version as usually printed, with the marginal notes and references of the Edition of 1611; the spelling of these conformed to modern usage. In the left-hand margin are also placed, in square brackets, the more important differences between the edition of 1611 and the text now in use, whether these differences are due to corrections of the edition of 1611 or to errors that have subsequently crept in."

In spite of all these facts, many ill-informed readers of the English Bible take the punctuation as "Gospel truth" and not only build their own theories and bolster up their traditions upon it but treat as heretics and cast out almost as apostates anyone who dares to question the authority of this human interference with the Word of Truth, if it should run counter to their Traditions, which are generally based on such human foundations.

In view of this indefensible attitude, we shall have to show its utter groundlessness.

It is beside our present object to enumerate all the cases where the punctuation has been changed, though all are of interest, and many are of importance.

These changes may be classed under three heads.

- Where the Edition of 1611 is to be preferred to the later Editions.

- Where the changes in the later Editions are improvements and

- There are other proposed changes which we suggest as being most desirable.

We shall proceed to give a few examples under each of these three heads.

(1) Changes in punctuation where the Edition of 1611 is certainly preferred to the later Editions.

1 Kings 19:5, "And as he [Elijah] lay and slept under a juniper tree, behold then, an angel touched him." In 1769, this was altered to "behold, then." This comma after "behold" has continued to the present day.

Nehemiah 9:4, "Then stood up upon the stairs of the Levites, Joshua, &c." In the Edition of 1769, this was changed to "Then stood up upon the stairs, of the Levites, Joshua."

Psalm 79:11, "Come before thee, according to the greatness of thy power: Preserve thou, etc. instead of "come before thee; according to the greatness of thy power preserve thou." This change was made in 1769.

Psalm 89:46, "How long, LORD, wilt thou hide thyself, for ever?" instead of "How long, LORD? wilt thou hide thyself for ever?" The third comma of 1611 was removed in 1629,* 1638, 1744, 1769, and in the current editions.

* Not 1630. In 1762, this comma was replaced by a semicolon.

In Proverbs 1:27, the final colon of 1611-1630 after "cometh upon you" is preferable to the present full stop, introduced in 1629 and retained in the current editions.

In Proverbs 19:2, the comma before "sinneth" should be restored, which was discarded in 1762.

In Proverbs 21:28, the comma before "speaketh" should be restored, which was removed in 1769.

Hosea 7:11, "a silly dove, without heart" instead of "silly dove without heart," since 1629; as though the last two words related to the dove, instead of to Ephraim.

John 2:15, "and the sheep and the oxen." In 1630 (not 1638 and 1743), 1762, and current editions, a comma was introduced after "sheep."

John 18:3, "a band of men, and officers." 1769 the comma after "men" was dropped; hence, the Roman cohort was not distinguished from the Jewish officers.

Acts 11:26 "taught much people, and the disciples were called." This was so from 1611 to 1630, both clauses being dependent on the verb "it came to pass." Two things came to pass: (1) that the people were taught, and (2) that the disciples were first called Christians. But in 1638-1743, the comma was replaced by a semicolon, and in 1762 by a full stop: the latter being quite against the Greek.*

* The RV goes back to the semicolon but not to the comma of 1611.

2 Corinthians 13:2, "as if I were present the second time." This was so pointed from 1611-1762. But since 1769, a comma is inserted after "present," connecting "the second time" with the foretelling instead of with the being present.

Colossians 2:11. The comma was removed after "flesh" in 1762, thus making one statement instead of two. The two clauses begin with en th (en te)—"by the putting off" and "by the circumcision of Christ." That is to say: "In whom (Christ) ye are circumcised with a circumcision not done by hand, by the stripping off of the* body (i.e., the flesh),** by the circumcision of Christ." Thus, this comma after "flesh" makes the last clause explanatory of the one preceding it and shows that in Christ, there is something more than the stripping off the old nature, which is sinner ruin; even the flesh itself, which is involved in creature ruin.

* All the textual critics with RV omit "of the sins."

** Genitive of Apposition.

2 Thessalonians 1:8, "in flaming fire, taking vengeance." By removing this comma in 1769, the "fire" is wrongly connected with the "vengeance" instead of with the being "revealed" in 2 Thes. 1:7.

Hebrews 2:9. The comma was removed in 1769 after the word "angels," compelling us to connect "for the suffering of death" with Christ's humiliation instead of His crowning. If we rightly divide these words, the suffering will be practically put in parenthesis by the two commas, thus: "We see Jesus who was made a little lower than the angels, (for the suffering of death crowned with glory and honor), that he by the grace of God, should taste death for every* man." This comma is wrongly replaced in the RV.

* I.e., every, without distinction, not without exception.

Jude 1:7, "the cities about them, in like manner." The comma after "them" was removed in 1638 and 1699 (not 1743), while in 1762, it was placed after "in like manner," thus increasing the error.

(2) Changes in punctuation where the later editions of the AV are improvements.

These hardly need enumeration, seeing that they are not likely to be missed. We may, however, note a few:—

Matthew 19:4-5. In 1611, the mark of interrogation was placed at the end of Matt. 19:4, but for many years, it has been removed to the end of Matt. 19:5.

John 12:20, "And there were certain Greeks among them, that came up to worship at the Feast." This needless comma after "them" was not removed till 1769.

Titus 2:13, "The appearing of the great God, and our Saviour Jesus Christ." This misleading comma, after "God," lingered till 1769, thus hiding the fact that only one Being is spoken of, viz., "God even our Saviour": i.e., our great Saviour-God, Jesus Christ.

Luke 23:32, "And there were also two other malefactors, led with him to be put to death." This, of course, practically classed the Lord Jesus as being one of three malefactors. But since 1817, a comma has been placed after the word "other," to avoid this implication.*

* This is far better than changing "other" to "others," as is done in the American Bible, 1867. This antiquated plural is continued in the American Edition of the RV of 1898.

Acts 27:27, "as we were driven up and down in Adria about midnight, the shipmen deemed that they drew near to some country." Not until after 1638 was the comma removed from after "midnight" and placed after "Adria"—"driven up and down in Adria, about midnight the shipment deemed," &c.

(3) Changes in punctuation, which are now proposed as being most desirable.

These proposed changes are improvements in the punctuation of the Edition of 1611 and subsequent editions. These suggestions are made from a better understanding, closer study of, and respect for the Context, as modifying or correcting traditional interpretations.

That we are more than warranted in such an attempt is shown by the Revisers in a note they affix to Romans 9:5. In this passage, in all the editions, the full stop is placed after the word "ever," thus: "Of whom as concerning the flesh Christ came, who is over all, God blessed for ever. Amen."

This text, being so weighty in witnessing to the Godhead of the Lord Jesus, was evidently distasteful to the Socinian member of the Company of Revisers, and, judging from the note placed in the margin, one can imagine what line the discussion had taken. All other marginal notes in the RV refer either to alternative renderings that affect the Translation or to ancient manuscript "Authorities" that affect the Text. There is no example, so far as we have seen, where interpretation has been introduced or where there is any reference to the interpretations of commentators. But here, there is the following lengthy marginal note, which exhibits the compromise reached by the Revisers and the Unitarian. They evidently declined to touch the Text, and consented to put this note in the margin. Its intention will be at once seen:

"Some modern interpreters place a full stop after the flesh, and Translate, He who is overall be (is) blessed for ever:* or He who is over all is God blessed forever. Others punctuate, flesh, who is over all, God be blessed forever."

* What is to be done with the "Amen," in this case, is not stated.

The object of this note is too painfully apparent, but it shows how important is the subject of punctuation. Moreover, it justifies us in not only calling attention to faulty punctuation but in suggesting changes where improvements may be made, which do not touch vital truth except to strengthen and enforce it. Whereas sad to say, some of the changes made by the Revisers are, unfortunately, those which interfere with the Deity of Christ, the Inspiration of the Scriptures, or the freeness of God's grace.

In 2 Samuel 23:5, if we make the last clause a question instead of a statement, we get the clue to a better rendering of the verse.

As it stands in the AV and the RV, it is difficult to make any sense of the verse at all. Not seeing the Structure or the true punctuation, the Translators were obliged to make it a statement.

If we ask what the word "so" (in 2 Sam. 23:5) means in the first line, we have the answer in 2 Sam. 23:4, where we have a description of God's King, and David immediately adds that it will be even so with himself as God's King and with his house in virtue of God's covenant (in 2 Samuel 7) with him and of the sure mercies of (or mercies made sure to) David.

In 2 Sam. 23:4, we have an alternation, the first and third lines speaking of the shining forth of God's light from heaven and its effect on the earth in the second and fourth lines.

2 Samuel 23:4

A. And He shall be as the light of the morning,

B. When the sun ariseth,

A. Even a morning without clouds;

B. When, from brightness and rain,* the tender grass shooteth out of the earth.

* So some Codices, with four early-printed editions, and the Sept., Syr., and Vulg. Versions. See Ginsburg's Heb. Text and note.

Then David goes on to say that, as that is a picture of what it will be, when He that ruleth shall rule righteously among men, ruling in the fear of God; even so will it be with his house and kingdom in virtue of the Covenant of God.

In 2 Sam. 23:5, the AV renders the word.

"Although," "yet," "for," and "although."

The RV renders them.

"Verily," "yet," "for," "although."

The Structure of the verse shows that the four lines are arranged as an Introversion, in which the first and fourth lines concern David's house, while the second and third lines are about God's covenant.

If we punctuate the first and fourth lines as questions, we may have this rendering, which certainly has the merit of consistency and clearness.

2 Samuel 23:5

C. "Verily, is not my house even so with God?

D. For He hath made with me an everlasting covenant, ordered in all things, and sure:

D. Now, this Covenant is all my salvation and all my desire,

C. For, Shall He not make it (my house) to prosper?"*

* Heb., to shoot forth, as the tender grass, as in line B. above.

We may take other examples where improvements can be suggested:—

Isaiah 64:5, "Behold thou wast wroth, and we sinned: in them have we been a long time, and, Shall we be saved?" In this case, the RV thus revises the punctuation of the AV to its great improvement.

Jeremiah 3:1. The last clause is evidently another question, repeating a similar question earlier in the verse: "And yet shalt thou return unto me saith the LORD?"

Matthew 19:28, "Ye that have followed me, in the regeneration when the Son of man shall sit on the throne of his glory, ye also shall sit upon twelve thrones, judging the twelve tribes of Israel." This was the punctuation of 1611, which was continued till 1629. But in 1630, a comma was introduced after "regeneration," which entirely altered the sense. It has, happily since been removed from our modern editions. This improvement should be noted and retained.

Luke 16:9, "And I; say I unto you 'Make to yourselves friends by means of the unrighteous mammon; that, when ye fail,* they may receive YOU into the everlasting habitations?' [No!**] He that is faithful in that which is least is faithful also in much; and he that is unjust in the least, is unjust in much also. If therefore YE have not been faithful," etc.

* "When it shall fail," according to Lachmann, Tischendorf, Tregelles, Alford.

** Beza's Latin and Grashop's English Version both put a full stop after "you." Beza begins the next sentence, "Certe" (surely); Grashop begins it, "Wherefore." We begin it "No!"'

The context clearly shows that Christ is contrasting and not identifying human and Divine modes of judgment. his context (Luke 16:10-12), and the logical conclusion of the parable have no meaning whatever unless the commendation of the unjust steward's lord is set in contrast with the condemnation of Christ. These verses (Luke 16:10-12) are not mere independent irrelevant statements but the logical conclusion to the whole argument.

The reception into the "everlasting habitations" of Luke 16:9 is set in contrast with the unjust steward's being received "into their houses" (Luke 16:4); the principles that govern admission there are the opposite of those that obtain admission here.

Hence, our Lord follows this up by adding the great lesson in Luke 16:10: "He that is faithful in that which is least is faithful also in much! and he that is unjust in the least is unjust also in much. If you have not been faithful to the unrighteous mammon, who will commit the true riches to you? And if ye have not been faithful in another man's, who will give you that which is our own" (see RV margin).

Luke 16:22-23. As at present translated and punctuated, the words read: "the rich man also died and was buried; and in hell, he lift up his eyes." But if we substitute Sheol or Hades for "hell," then we have (as in Isaiah 14:9-20) a representation of dead people talking, as we have of the trees talking in Jotham's parable (Judg. 9:8-15). If we further observe the Tenses and Moods of the verbs and repunctuate the passage, we have the result as follows:

"The rich man also died and was buried also in Hades. Having lifted up his eyes, being in torments, he seeth." There is no "and" before "seeth." It is not an additional statement, "and he seeth," but a second verb, depending on the participle "having lifted up his eyes."

The Greek necessitates this change in translation, and the change in punctuation is not suggested as a modern invention to support any particular interpretation, for it is that adopted in the ancient Vulgate translation, which, though not the original text, and of no authority as a text, is yet evidence of a fact. It is punctuated in the same way by Tatian, Diatessaron (AD 170), and Marcion (AD 145), as well as in the ancient Jerusalem Syriac Version. The fact is that the first three words of Luke 16:23 form, instead, the last three words of Luke 16:22, a full stop being placed after the word Hades, while the word "and" is treated by this as meaning "also." So that the whole sentence would read thus: "But the rich man also died and was buried also in Hades."

"Buried also" implies what is only inferred as to Lazarus, meaning that the one was buried as well as the other. Whether the punctuation is allowed or not, it does not affect the matter in the slightest degree. For that is where he was buried in any case. It affects only the place where he is said to lift up his eyes.

This is further shown by the fact that the three verbs "died," "buried," and "he lift up" are not all in the same Tense as they appear to be from the English. The first two are in the past tense, while the third is the present participle (eparas), lifting up, thus commencing the 23rd verse with a new thought.

Those who interpret this passage as though Hades were a place of life instead of death make it "repugnant" to every other place where the word occurs and to many other scriptures which are perfectly plain, e.g., Psalm 6:5, Psa. 31:17, Psa. 115:17, Psa. 146:4, Eccl. 9:6, Eccl. 9:10. (See Canon VII, Part II).

Luke 23:43, "Verily, I say unto thee, to-day shalt thou be with me in paradise."

This is the common punctuation, but Is it correct? We have already seen enough to show us that we are dependent only and entirely on the context and on the analogy of truth.

The word "verily" points us to the occasion's solemnity and the importance of what is about to be said. The solemn circumstance under which the words were uttered marked the wonderful faith of the dying malefactor, and the Lord referred to this by connecting the word "to-day" with "I say." "Verily, I say unto thee this day." This day, when all seems lost, and there is no hope; this day, when instead of reigning, I am about to die. This day, I say to thee, "Thou shalt be with me in paradise."

"I say unto thee this day" was the common Hebrew idiom for emphasizing the occasion of making a solemn statement (see Deut. 4:26, Deut. 4:39-40, Deut. 5:1, Deut. 6:6, Deut. 7:11, Deut. 8:1, Deut. 8:11, Deut. 8:19, Deut. 9:3, Deut. 10:13, Deut. 11:2, Deut. 11:8, Deut. 11:13, Deut. 11:26-28, Deut. 11:32, Deut. 13:18, Deut. 15:5, Deut. 19:9, Deut. 26:3, Deut. 26:16, Deut. 26:18, Deut. 27:1, Deut. 27:4, Deut. 27:10, Deut. 28:1, Deut. 28:13-15, Deut. 29:12, Deut. 30:2, Deut. 30:8, Deut. 30:11, Deut. 30:15-16, Deut. 30:18-19, Deut. 32:46).

"Paradise" was the condition of the earth before the entrance of Satan and the pronouncing of the curse, so it will be the condition of the earth again when Satan shall be bound, and the Lord shall come and reign in His Kingdom. It is called in Hebrew "Eden" sixteen times and "The Garden" nineteen times. The Greek for these is Paradisos (which we have changed to "Paradise"). It is never used in any other sense than of a place of beauty and delight on the earth. Never of any place above or under the earth. "The Tree of Life" and "The River of the Water of Life" are its two earthly characteristics. The traditional idea of any other place is unknown and foreign to Scripture and is the pure invention of fallen man. It comes down to us from Babylon through Judaism and Romanism.

We see it described in Genesis 2, lost in Genesis 3, and its restoration pronounced in Revelation.

We hope these few examples help to illustrate the painstaking research that goes into working the Ancient Texts and highly recommend to those not inclined to undertake detailed word studies from the originals to utilize the wonderful resource called The Companion Bible that our dear Dr. Bullinger spent so many years of his life to produce under the watchful instruction of The Holy Spirit.